Natural History

Watercolor of Wasps by Jean-Gabriel Prètre (1775-1840)

Jean-Gabriel Prètre was a Swiss-French painter and illustrator known for his natural history paintings and illustrations featuring birds, mammals, and reptiles. His watercolor and gouache works on paper appear as illustrations in many books, including Flore d’Oware et de Benin (1804).

Born in Geneva in 1775, Prètre began his career as an illustrator documenting the fauna at Empress Joséphine Bonaparte's horticultural haven and menagerie at the Château de Malmaison. Following her separation from Bonaparte in 1809, Joséphine stewarded Malmaison into a flourishing botanical center and home to fauna that roamed freely among its grounds and gardens. Prètre’s depictions of these insects and animals reflect the opportunities for artists to study and produce reproductions of flora and fauna specimens. Prètre later went on to work as an illustrator for the Natural History Museum in Paris. Read More

botanical paintings by Barbara Regina Dietzsch (Nuremberg, 1706-1783)

Barbara Regina Dietzsch, born on September 22, 1706 in Nuremberg, Germany, painted with gouache on vellum to create luminous, dramatic renderings of flowers and their insects on dark backgrounds. Her work was greatly admired and collected during her lifetime and are now considered exemplars of 18th century natural history renderings. While many of Dietzsch’s judiciously depicted gouache botanicals were transposed into plates for engravings in natural history books, her artistry pushed these paintings beyond the bounds of natural history illustrations.

Dietzsch was the eldest child in an artistic family. Her father, the landscape painter Johann Israel Dietzsch, taught her to paint with gouache on vellum. Barbara Regina in turn taught her younger sister Margaretha Barbara Dietzsch (1726-95), who became an accomplished engraver and botanical painter. Dietzsch’s paintings are in private and public collections, including The National Gallery of Art, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Baltimore Museum of Art and The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Italian Studies of a Lemon by Vincenzo Leonardi (c. 1590-1646)

Vincenzo Leonardi was an Italian artist active in Rome from 1621-1646. A master of naturalistic illustration, Leonardi was commissioned by Cassiano dal Pozzo to create watercolor drawings of natural history for Cassiano dal Pozzo’s Museo Cartaceo (“Paper Museum”). Leonardi’s Two Studies of Lemons features a lemon viewed both externally and sliced open, one of many examples of Dal Pozzo’s collection documenting the citrological world in visual and textual form. Dal Pozzo’s collection of works on paper reflects interest among Rome’s cultural and intellectual circles in the classification and taxonomy of natural history. Read More

Watercolors of Butterflies and Moths

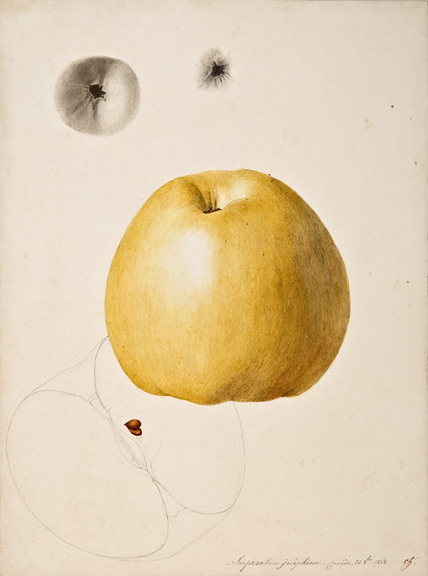

French Watercolors of fruit by Anthelme-Eugene Grobon (1820, Lyon - 1878, Grigny/Rhone)

Anthelme-Eugène Grobon was a French artist known for his studies of natural history and plant specimens. A key contributor to the field of ecology painting in the 19th century, Grobon studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon from 1834-1835 and 1840-1841. With his brother François Frédéric Grobon (1815-1902), he co-authored several published collections of hand-coloured prints of flowers between 1844 and 1850. The Grobon brothers also published an instruction manual for flower painters, Méthode Grobon frères, études progressives de Fleurs et de Fruits, depuis les premiers éléments jusqu' à la composition des groupes (Paris, 1850). Anthelme-Eugène Grobon is recorded as having exhibited at both the Lyon Salon (from 1838) and the Paris Salon (from 1852 through 1870). Read more

French Watercolor of a Pear by Louis-Pierre Riocreux (1791- Sèvres 1872)

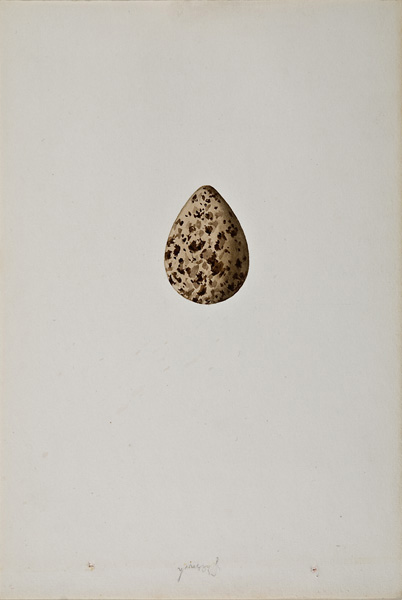

French watercolors of eggs

French watercolors of squash

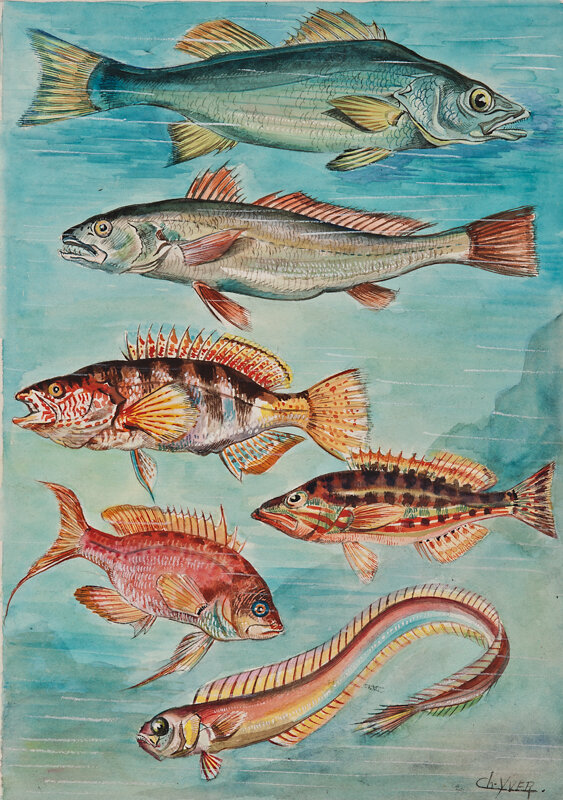

Watercolors of fish by Charles Yver, 1941

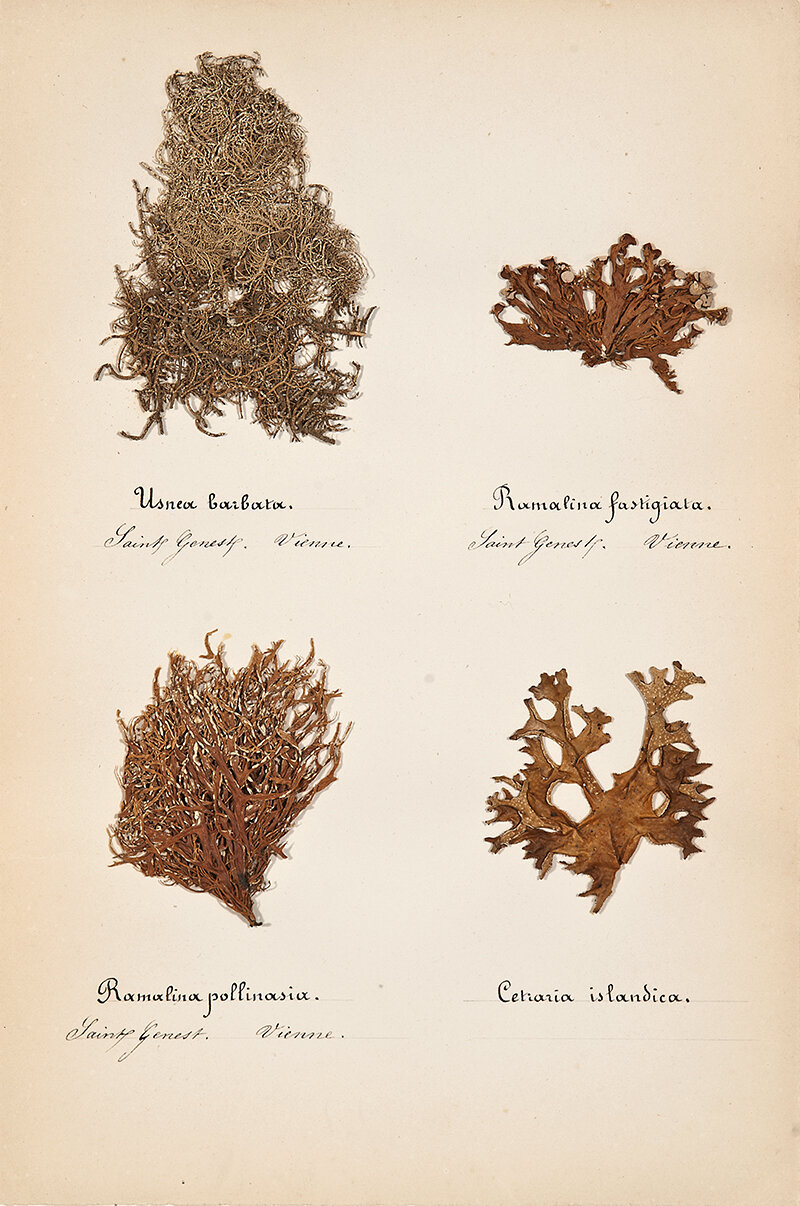

French Herbaria: Mosses

Herbaria are preserved specimens of plants, often organized and classified with their associated data used for scientific study in collections known as herbarium. Herbaria may include a whole plant or its fragmented parts, with plant specimens mounted on thin sheets of paper called flimsies. While mounting techniques vary, those utilized in these nineteenth century samples include an applied gluing technique or one in which paper splices form tabs to hold the delicate specimens in place.

Some of the earliest recorded herbaria were established in Europe in the early 1600s, when European scientists sought to record, study, classify and ultimately understand the plant world. Due to an acceleration in European exploration and colonization, collections of flora specimens grew in accumulation and at a pace at which botanical gardens were no longer capable of maintaining living examples of each species. As such, herbaria came to support and expand botanical study through their smaller scale, portability, and capacity for preservation beyond the lifespan of a living plant.

Herbaria have been collected for centuries by botanists, laboratories, museums, libraries, and individuals for purposes ranging from scientific study to an intrigue in the visual form of the flora. In addition to the widespread scientific practice of collecting and preserving herbaria, amateur botanists discretely collected samples of their own, and were known to have preserved and presented their specimens with unique stylistic choices, often without the extensive categorical labelling system common to scientific herbaria. Such intimate samples of herbaria reference historical collecting practices of material culture; the flora pressings mounted on paper echo scientific botanical presentation, while adjusting to the aesthetic and decorative trends for the domestic sphere.

As objects of material culture, herbaria uniquely combine scientific documentation with a rich visual composition. Plant specimens typically include flower/fruit, as they are gathered when reproductive structures are present to aid in complete identification and taxonomy. As such, the samples present a visual presentation of plant life that bears no relationship to facsimile nor mimesis, unlike the related representational practices of botanical illustration or realism. Language aids the visual presentation, as labels are critical to the complete documentation of flora specimens. For botanists, the label on an herbaria sample is just as important as the specimen itself. While labelling systems vary, they typically include the specimen’s family name, genus, species, location, habitat, collector name, and the date. These 19th century herbaria samples include various algae, mosses, grasses and flowers. This collection demonstrates the varying practices and arrangements for preserving and presenting flora.

French Herbaria

FRESH WATER FISHES OF GREAT BRITAIN BY SARAH BOWDICH (BRITISH, 1791-1856)

Sarah Bowdich (1791–1856) was an English author, illustrator and ichthyologist. Her sole-authored natural history of Fresh Water Fishes of Great Britain, c. 1828, features twenty-one lifelike illustrations of fish. During a time when the majority of international scientific expeditions were exclusively male, Bowdich was a rarity. Her illustrations are not only scientifically accurate but also demonstrate her considerable understanding of the medium to achieve these lifelike renderings. She worked, in her own words, “from the living Fish immediately as it came from the water it inhabited; so that no tint has been lost or deadened, either by changing the quality of that element, or by exposure to the atmosphere.”